The students at Drayton Hall Elementary in Charleston, SC generally start each morning a bit differently than many other schools. After attendance and the Pledge of Allegiance, they pull out their iPads and get to work. And sometimes that schoolwork might appear to be less about memorizing facts and figures and more about having fun.

That’s an illusion, though. Apps used in the school, such as Popplet, help the students better retain information that they might breeze by in a textbook by presenting it as though it’s part of a video game.

Drayton Hall is an Apple Distinguished School, a certification the company gives to what it considers some of the most innovative schools in the world. And it has been incorporating gamified learning into its curriculum since 2011.

Video games might be designed to entertain, rather than educate—but as these students (and graduates of the school) can testify, there’s often a lesson hidden amidst the fun. And sometimes, it’s the best way to learn something.

There are, of course, the obvious life lessons video games teach, such as self-regulation, collaboration and creative thinking. Few titles, after all, can be won without failing several times. By encouraging players to try again and seek help from outside resources, video games teach students to utilize those same sorts of problem-solving skills to academic problems.

Many titles can also reflect the academic interests of the player. Civilization VI players, for instance, might enjoy the historical elements or the engineering aspects of the game. Virtually any real-time strategy game includes economic and budgeting as part of the game. And a die-hard MMO (massively multiplayer online) player who maxes out their character’s spell-making skill could have a real-world interest in chemistry.

But researchers are increasingly finding that games can be educational vehicles that help players in a variety of other ways as well.

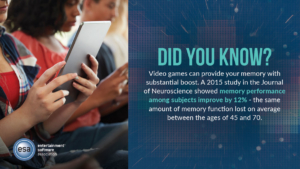

A study at the University of California, Irvine, reported in the December 2015 edition of The Journal of Neuroscience, found that three-dimensional video games can boost the formation of memories—substantially. Memory performance among test subjects increased by roughly 12%. That’s the same amount most people’s memory decreases between the ages of 45 and 70.

Nintendo, meanwhile, partnered in 2018 with the educational nonprofit Institute of Play to launch a pilot program in 100 schools nationwide for children between the ages of 8 and 11 centered around the Nintendo Switch and Nintendo Labo kits. The project focused to honing the critical thinking skills of kids in the fields of science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics. (Students worked in small groups to create a series of projects, and teachers were given suggested lesson plans, classroom management tools and advice on how to incorporate Nintendo Labo into their curriculum.)

While Nintendo focuses on younger students, the North American Scholastic Esports Federation is targeting 9th to 12th graders, with a series of integrated courses that were meant to replace traditional high school English classes. (Rather than reading Shakespeare, students develop their English-language skills by writing about topics such as the history of esports or comparing video game characters to mythological heroes from literature.

One of the biggest advantages video games have as educational tools, however, is they teach lessons in the context of play, rather than work. That encourages kids who might otherwise be less motivated to learn, since they see edutainment titles as a distraction from the day to day of school rather than a part of it.